Sam Herron

Sam Herron

Sam Herron never thought he'd be living in his car. Not at 50, not after the extraordinary life he'd led. In the late eighties, Herron was playing bass in the hard rock band, Grave Danger when he and his bandmates landed a major-label record deal. They had a big, arena rock sound, full of soaring vocals and nitro-charged guitar solos, but also a hint of arty weirdness thanks to Herron's eclectic tastes.

They recorded two full-length albums that, thanks to the back-room machinations of the label's management, never made it to stores. The band was poised to tour with AC/DC when Universal bought them out of their contract, nullifying Herron's dreams.

Heartbroken, Herron put his bass in the closet and focused his energy on what is still an unlikely profession for a tatted-up gearhead with long hair: trading stocks. Over the next several years, he parlayed the minor windfall he received from the record company into a sizable fortune.

With the knowledge and connections he'd made with entertainment-industry execs in Los Angeles, Herron combined his indefatigable intelligence with a relentless Midwestern-bred work-ethic to great success. He made more money than a kid growing up in Aurora, Illinois could reasonably expect, and he made sure to enjoy it, spending much of his wealth on good food, travel, motorcycles, party supplies, and spoiling his friends. The loss of his mother, followed by the unexpected deaths of his two best friends sent him into a downward spiral that lasted fifteen years.

Eventually, he ended up downsizing from house to condo, then condo to friend's apartment. Out of desperation, he took a job working on pivot irrigation systems in Omaha, Nebraska. It was a kind of bittersweet homecoming—Herron's first job out of high school had been punching metal in an Illinois factory.

With his solid, 6'2” frame, Herron had always enjoyed working manual labor jobs. But hefting sheets of metal and wielding a lathe in a sweltering factory in high July is a different prospect at age 50 than it is at 18. Herron couldn't maintain his equilibrium in that atmosphere anymore—two dormant hernias and an old shoulder injury started haunting him again. Eventually, he suffered a career-ending bout with heatstroke.

Now unemployed, with no college degree, marketable skills or consistent work history, Herron struggled to find a job. His relationship with his girlfriend started failing. He started drinking with extreme stress and the lingering effects of his workplace injury.

In February of 2012, shortly after Valentine's Day, he woke up in his car on a bridge in Omaha, with no money, no place to go, no family to rely on, and no idea what to do. He found himself in a situation absurdly at odds with his younger self. Faced with the dilemma of seeking a warm bed in a homeless shelter or keeping his freedom and freezing in his car, he froze.

As winter turned to spring and a promising job failed to materialize, Herron feared he'd never wake up in a room of his own again. He often went for several days without food, spending what little money he could scrounge on beer, coffee, cigarettes. and gasoline. Still, every morning he bathed in the Men's room sink of a local coffee shop, shaved, brushed his teeth and donned job-interview clothes on the off-chance he might make a connection that would lead to work.

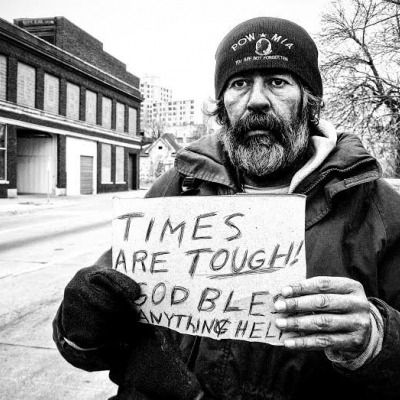

A few months into his homelessness, he started keeping a blog about his experience. He kept his old friends updated via Facebook. At his lowest ebb, he picked up one of the few things he'd managed not to sell—a digital camera purchased at an Omaha pawn shop. Despite never having considered himself a photographer, Herron started documenting his life on the street. With the laser-eye immediacy and empathy forged by his experience, he managed to capture the grit and horror of being homeless in a series of black-and-white photographs—candid street portraits of down-and-out individuals—influenced as much by Great Depression-era documentarians like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans as by modern masters like Daido Moriyama and James Nachtwey.

As the audience for his photography grew, Herron found himself in the unusual position of becoming a rising star in the local art scene—a scene shored up by the free wine and cheese at gallery openings and high-concept lectures at universities and museums—while literally starving to death in his car. In a stroke of luck, he met an 84-year-old photography enthusiast and widower who had a habit of providing shelter for talented but struggling men. The man offered Herron a free room, friendship, and the benevolent injunction to keep working on his art. After four months on the street, with increasingly dimming prospects, Herron suddenly had a home and a full-time project to work on: chronicling the lives of the dispossessed.

The project grew into his first solo exhibit, "Street Life Chronicles," held at Omaha's Creighton University, to broad acclaim. Herron's journey was even spotlighted in an Omaha World-Herald cover story.

The sudden influx of attention, coupled with his increasing desire to address a persistent societal tragedy, encouraged Herron to keep developing "Street Life Chronicles." His first-person accounts of the street, written under duress of experience, had garnered some attention from his followers.

Before Herron made it off the street, a professor in Vermont suggested Herron transform his writings into a hard-edged book bearing the influence of heavies like Charles Bukowski and Henry Rollings. The professor offered him a chance to move to Vermont and finish the book. A day before he was to sell his car and buy a one-way train ticket east, the deal fell through and the book was put on hold.

In December 2013, a chance encounter with the writer Tom McCauley rekindled the book idea. The two began fleshing out Herron's experience, as well as the stories of the people in his photographs, into a full-length book. A polyphony of voices, perspectives, illness, photographs and impermanence, "Live Through This" tackles issues of alienation and communion in the intractable economic dysthmia of post-recession America. It reaches beyond mere memoir, documentary, anthropology or art into the realm where all things go to make a beautiful, terrible noise.

Meanwhile, Herron continues to work, wringing art from a pawnshop camera with the painstaking patience of a man who accepts he has no idea what's coming—like all of us, whether we admit or deny it. Take a few minutes to see what the world looks like: www.facebook.com/samuelherron.

— Tom McCauley

“I’m a total letdown for daytime talk shows that test DNA samples. No biological children. I have no hobbies and I never relax.” — Sam Herron Photojournalist/Photographer